I’m pretty sure every writer with a blog, a book, or a buddy with half an ear has an opinion about the necessity of outlining their story. From the Snowflake Method to simply winging it, there’s a plethora of strategies. I don’t have a catchy name for mine, but I do have a diagram.

For the purpose of this post, I’ll be focusing on novel and feature screenplay outlines. You can use this outlining strategy for writing a pilot, but I’ll save the nuances of pilot writing for a separate post.

Conflict Brainstorm

I usually have a vibe, a built-ish world, fleshy characters, and the broad strokes of conflict figured out before I begin worrying about the plot. (As a sci-fi/fantasy writer, I wouldn’t have anything to base my plot ideas off of otherwise.) Then I brainstorm a bullet point list of potential conflicts, exploring any ideas and what ifs that come to mind. Especially the stupid ones! Those “stupid” ideas that “probably” won’t go anywhere likely have a good idea several layers below it. Besides, it’s satisfying. Let yourself have fun and save the seriousness for your third and fourth drafts.

If you need to switch gears to restructure a character or debate the commonality of certain foods, do it! This is a brainstorm. The conflict can wait until you have something to bounce it off of. The best ideas require a little digging.

Plot Lines

As you brainstorm, consider the plot lines you want to focus on. The biggest ones will center your protagonist’s internal and external conflicts.

An external conflict is a problem that the protagonist faces in the world. It’s the protagonist against a rival, an aspect of the world, or something else out of their control.

An internal conflict is the protagonist against an aspect of themselves. This could be choosing between two desires, an aspect of their personality that gets in the way of their goals, or a lie that they believe about the world.

You’ll also have subplots referred to as the b-story, c-story, and so on. These subplots enhance the narrative in some way. Oftentimes they focus on a relationship, address the theme from a different angle, or show the antagonist’s point of view.

In The Hunger Games, Katniss wants to survive so she can get back to her sister. (External conflict.) She has to grapple with her humanity, because she isn’t bloodthirsty like the tributes from Districts 1, 2, and 4. (Internal conflict.) She also cares about Peeta, who made his feelings for her public knowledge before the games began. (B-story.)

Katniss’s internal conflict (and the star-crossed lovers subplot) gets in the way of her external goal. In the end, winning isn’t worth killing Peeta and a revolution is born as a result.

Even if the narrative never directly states the internal conflict (as films rarely do), the internal conflict still influences the protagonist. It’s the job of filmmakers and actors to convey what they can, but narrative actions speak louder than words. The audience will feel the echoes of the internal conflict from the protagonist’s actions and reactions. If you don’t bake it into the narrative, your story will feel empty. The Hunger Games wouldn’t have been a hit if Katniss ruthlessly killed Rue, Peeta, and everyone else in the name of survival.

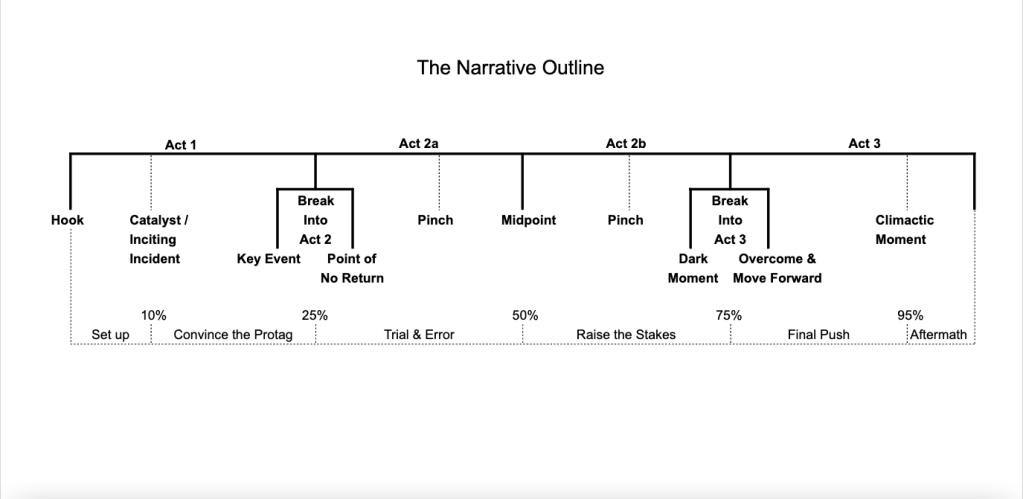

Act Breakdown

As I brainstorm, I end up with a list of potential scenes. It doesn’t matter that most of these ideas will end up in the trash. I need something to sort through as I put together the act breakdown.

The act breakdown is a summery of each act. The summary can be as long or as short as you need, but I try to simplify it to a single sentence by the end of the process.

To start, separate a piece of paper into four sections and label them act 1, act 2a, act 2b, and act 3. A major turning point happens at the end of each act, causing the protagonist to pivot. Now ask yourself: What are those major events? How do these events alter the protagonist’s story goal?

Act 1 must convince the protagonist to enter the new situation that the story is about. Act 2a pushes the protagonist to have a Moment of Truth, which will turn the story in a new direction. Act 2b raises the stakes as they figure things out and eventually reach a low point. Once they overcome that low point, they enter act 3 and the final confrontation.

Breaking the story down like this helps to ensure the major turning points are actually moving the story forward. If you find yourself struggling to come up with solid turning points, try moving aspects of your story around. Maybe the climax you’ve been envisioning belongs in the middle of the story. Maybe the protagonist has to grow in a different way, which leads to you altering the internal conflict.

Once you have an idea of what each act accomplishes, you can start sorting your scene ideas by acts for a better sense of what needs to happen and when.

Loose Outline

Depending on the story, I might fill out my loose outline in tantum with my act breakdown (or completely redo my act breakdown after I solidify my loose outline.) This gives me a solid roadmap to follow as I write my first draft.

My loose outline consists of describing the events that take place at key points in my story. I’ll describe each point below.

I included a pinch point before and after the midpoint. Ignore these pinch points until the rest of your outline is figured out. Their purpose is to raise the stakes in the middle of act 2a and act 2b, which helps to avoid a “sagging middle” where the audience loses interest in the story due to iffy pacing.

I find that pinch points come to me naturally during my outline brainstorm or as I’m writing the second act. Either way, the rest of the outline should be solid before you worry about how to pace your second act.

The Plot Beats

Act 1

Hook: The first scene of the story. How can we peak the reader’s interest while acclimating them to the story?

Catalyst/Inciting Incident: This is the call to adventure, where the story’s conflict is introduced or an opportunity is presented to the protagonist. Their world will never be the same even if they try to refuse the call.

Key Event/Break into Act 2: The protagonist decides to take the opportunity and pursue the story’s main objective.

Act 2a

Pinch: A point of tension. The stakes are heightened as the protagonist brushes against the antagonist or makes progress towards their goal. Often times, they’re punished for using their misguided belief/the lie that they believe.

Midpoint: The moment of truth. The protagonist has a breakthrough realization about the conflict that turns the story in a new direction. They see through their misguided belief, but can’t yet let go of the lie.

Act 2b

Pinch: A point of tension that complicates the conflict. Often times, they’re rewarded for using the truth instead of the lie.

Low Point/Dark Moment: At this point, the protagonist is furthest from reaching their goal. They must deal with a major setback. They learn to reject the lie in order to move forward.

Act 3

Climax Begins/Break into Act 3: The protagonist overcomes the low point, regroups, and goes head to head with the antagonist. This is the final push to end the conflict. It shows them embracing the truth.

Climactic Moment: The protagonist’s final confrontation with the conflict. The protagonist fails or succeeds, after which the major dramatic question is answered and the conflict ends.

The Hunger Games Outline

Act 1 (Goal: Protect Prim at all costs.)

Hook: Katniss wakes up. Her very first concern is her sister Prim and how the reaping has emotionally affected her.

Catalyst/Inciting Incident: Katniss volunteers as tribute in place of Prim.

Key Event/Break into Act 2: Katniss and Peeta leave for the Capitol.

Act 2a (Goal: Prep and strategize for the games.)

Pinch: During the interview, Katniss grabs the viewer’s attention with a fiery dress and Peeta tells the public he’s always had a crush on Katniss.

Midpoint: The moment of truth. Is Katniss willing to do what it takes to survive?

Act 2b (Goal: Survive while maintaining her humanity.)

Pinch: Rue dies. Katniss couldn’t save her.

Low Point/Dark Moment: Peeta almost eats poison berries. Katniss realizes how deep her feelings towards Peeta are.

Act 3 (Goal: Keep both herself and Peeta alive during the final stretch of the games.)

Climax Begins/Break into Act 3: Katniss and Peeta fight Cato, the remaining tribute.

Climactic Moment: Katniss and Peeta survive, but are told they can’t both win. They decide to die together instead of killing each other. Before they eat the poison berries, they’re stopped by the game master. Both are named the winners.

Outline Brainstorm

From here, I flesh out the loose outline into an outline brainstorm. It’s the first draft of my official outline.

I give myself permission to write down whatever bullshit that comes to mind. I won’t hesitate to write down a “stupid” idea, because brainstorms are allowed to be stupid. (I can’t be the only one who has to play these mental games with myself.)

Between the major plot points, I’ll create a bullet point list of (potential) scenes. If, later, I think it works better at a different point in the story, I’ll move it. If it doesn’t feel right anymore but I can’t bring myself to delete it, I’ll strike through the bullet point.

When I have a solid grasp on the plot, I’ll start moving usable scenes to The Outline.

The Outline

The Outline is set up exactly like my outline brainstorm, but it’s cleaner and less cluttered. It’s not exactly a final draft because The Outline is a living, breathing document that I keep up to date as I write.

If I need to delete a scene from The Outline, I’ll recycle it to my outline brainstorm for safe keeping. Cutting content is easier when I’m not actually losing access to it.

The Pitfalls of Outlining

Keep in mind that outlining isn’t writing. Writing is writing.

Many writers fall into the trap of editing and re-editing their outline in order to procrastinate actually writing. (And by many I mean all. If their activity isn’t outlining, it’s chores, doomscrolling, planning a trip that might never happen, or writing a blog post about outlining. I’m not projecting. I swear.)

Some writers swear by having every single scene planned out before ever writing a word. If that works for you, that’s great, but I myself don’t always complete The Outline before I start writing. My exact process varies from story to story, as will yours, and prescribing to stiff rules will only hold you back. Once I have a solid, loose outline, I give myself permission to throw things into the manuscript document.

Outlines are great roadmaps, but do what feels right for you and your manuscript. Write a scene if you feel inspired to write it. Write scenes in or out of order.

At the end of the day, you practiced your writing skills and that is never a waste. It’s impossible to research everything in the pre-writing stage, so don’t hold yourself to that standard. Discovering the story is the fun of the first draft.

What strategies do you find helpful as you outline? Do you prefer to wing it? Let me know in the comments below!

Leave a comment